MvvmCross Overview

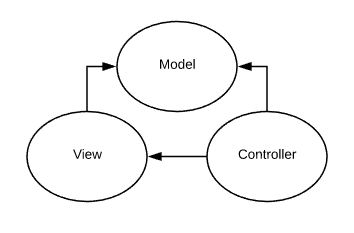

When I started working with Xamarin many years ago, I first worked with a project built with Model-View-Controller (MVC) design. MVC is pretty straightforward, you have a model for business logic, rules, and data, a view for the user to interact with, and a controller which is basically the middle-man between the model and view. A controller determines what view to serve to the user along with any model data it may require. The graph below is extremely simplified, but it shows the relation between each major component. Notice the model doesn’t have any arrows pointing away. This is due to the model not having any dependency on the view or the controller. This is helpful as you can build and test the model independently of the the view and controller. It’s a pretty common design pattern that’s been around since the 70’s. I enjoyed working with it, but I found myself writing a lot of boilerplate code in the controller to listen to view events and to return data back to the view.

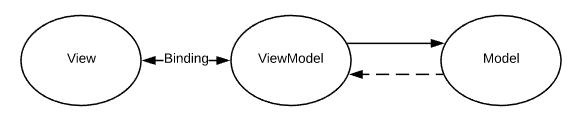

When working with a single platform/view type, the boilerplate code isn’t all that terrible, but when incorporating even a second platform or more, it starts to get repetive. For example, if you’re writing a mobile application in Xamarin for iOS and Android and you were using an MVC design pattern, you’d have controller logic for iOS and Android independently to handle user interaction, serve up views, and more. In order to solve the issue of writing all of the boilerplate code in the controller, we need some way to connect the view components directly to the data and vice versa. Instead of wiring up each individual click event or data entry independently on each platform, we want a way to do this simply and easily in a cross-platform fashion. Enter the Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) design pattern. A few architects from Microsoft created and incorporated the MVVM design pattern into Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) and Silverlight back in the early to mid 2000’s. The basic concept of MVVM is that you utilize something called binding between a view and a viewmodel. What this allows you to do is have a single viewmodel that can be utilized on multiple platforms to handle click events, text entry, and provide the state of the view at any time. This makes it extremely easy to connect your view to the data without writing boilerplate code as I mentioned above. Similar to MVC, you still use models to represent your domain model and business logic.

Xamarin has support for Data Binding out of the box, but only if you’re utilizing Xamarin.Forms as your view framework. If you’re like me and don’t use Forms, you’ll be stuck looking for an alternative. Fortunately there’s a few awesome open source projects that provide not only support for data binding, but a whole suite of additional tools and helpers to make writing great cross-platform apps even easier. Today we’ll be chatting about MvvmCross, but there’s many other good frameworks out there.

One quick note for those who use Xamarin.Forms, there’s a ton of reasons to utilize a framework like MvvmCross for data binding rather than the built it. Most of the extra tools the framework provides are hugely beneficial for Forms users as well.

MvvmCross

MvvmCross is an open source framework specifically built to be used with Xamarin. It has support for Xamarin.Android, Xamarin.iOS, Xamarin.Mac, Xamarin.Forms, Universal Windows Platform (UWP) and Windows Presentation Framework (WPF). The framework provides the core functions necessary to build a proper MVVM application with Xamarin, but also provides a plethora of helpful tools and helpers beyond that. It’s also easy to extend via Plugins and is extremely customizable, so you can mold it to fit your exact needs.

I am going to briefly cover some of the major features and benefits of the framework in this article, along with a few cons. I will take a deeper dive on some of the topics covered below in a future blog post.

Data Binding

The bread and butter of the MVVM design pattern and the MvvmCross framework. Being able to drive your view off of a ViewModel based on events is not only simpler, but also means more common-code between platforms and less boilerplate code. If you have a label on a screen representing a user’s account balance, you can drive that off of a C# property. Anytime the property changes, the view will automatically update to reflect the change (as long as you’ve raised the property event changed message in the setter). It also works similar for a text entry box. If a user is entering some text into a text field, you can bind that to a property, so the ViewModel always knows what the text on the screen is. Once they’ve entered the text, they’ll probably click a button. For click events like these, you can simply bind the click event to an ICommand, which executes when the user clicks the button. So now you can call a method to perform an action, and grab the text input from the property all without wiring up any platform-specific touch event listeners or extra code.

So how does that look in code? I’ll walk through the above samples of how they’d look for iOS and Android with Xamarin.Android and Xamarin.iOS.

First, we’ll start with the ViewModel. In this example, I won’t be using a Model, but in more complex examples you’d definitely want to utilize one.

class MyViewModel : MvxViewModel

{

private IService _service;

public MyViewModel(IService service)

{

_service = service;

SubmitMessageCommand = new MvxAsyncCommand(() => SubmitMessage());

}

private string _messageFieldText;

//The property that we'll bind the text input field to

public string MessageFieldText

{

get => _messageFieldText;

set

{

_messageFieldText = value;

RaisePropertyChanged(() => MessageFieldText);

}

}

//Text that we want to display on the button. This is hardcoded, but it can drawn from a Strings file, or use a ResxLocalization Plugin to support multiple languages.

public string SubmitButtonText => "Submit";

//ICommand that we register a new command for in the constructor that will get binded to in the View

public ICommand SubmitMessageCommand { get; private set; }

private async Task SubmitMessage()

{

await _service.SendMessage(MessageFieldText);

}

}

The above ViewModel is pretty straightforward and would exist in either a PCL or a Net Standard library to be referenced by your Xamarin.Android and Xamarin.iOS projects (as well as Xamarin.Forms). It uses ICommand’s to drive view events such as button clicks and other touch gestures.

Next, we’ll show how this binding would be connected within an Android layout file (.axml). You can also bind via C# code which I’ll showcase in the iOS example below, but I’ll just show the binding directly in axml.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<LinearLayout

xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android"

xmlns:local="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res-auto"

android:layout_width="match_parent"

android:layout_height="match_parent"

android:gravity="center"

android:orientation="vertical">

<EditText

android:layout_width="300dp"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

local:MvxBind="Text MessageFieldText" />

<Button

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

local:MvxBind="Text SubmitButtonText; Click SubmitMessageCommand" />

</LinearLayout>

Above is an extremely simple Android layout file. It’s just an EditText field and a Button. One thing extra here that’s not normal is the local:MvxBind field at the bottom of the EditText and Button. This is how we’re able to bind certain properties of a View component directly to the ViewModel. The framework will know to set the text of the button to the property in the ViewModel, which will be “Submit”. It also registers the click event of the button to call the ICommand in the ViewModel. Lastly, the EditText field will be bound to the Property in the ViewModel.

Last but not least is iOS. We’ll be writing the View code in C# in this example, but binding works great with Storyboard’s and XIB’s as well.

class MyView : MvxViewController<MyViewModel>

{

UITextField _messageField;

UIButton _submitButton;

public override void ViewDidLoad()

{

base.ViewDidLoad();

View.BackgroundColor = UIColor.White;

_messageField = new UITextField

{

BorderStyle = UITextBorderStyle.RoundedRect,

Frame = new CGRect(10, 82, View.Bounds.Width - 20, 30.0f)

};

_submitButton = UIButton.FromType(UIButtonType.RoundedRect);

_submitButton.Frame = new CGRect(10, 170, View.Bounds.Width - 20, 44);

_submitButton.BackgroundColor = UIColor.LightGray;

View.AddSubviews(_messageField, _submitButton);

//Here's what we care most about. We create a binding set and bind the _messageField to the MessageFieldText property in the ViewModel.

//We also bind the title and clicked events of the _submitButton to the ViewModel

var set = this.CreateBindingSet<MyView, MyViewModel>();

set.Bind(_messageField).To(vm => vm.MessageFieldText);

set.Bind(_submitButton).For("Title").To(vm => vm.SubmitButtonText);

set.Bind(_submitButton).For("Clicked").To(vm => vm.SubmitMessageCommand);

set.Apply();

}

}

Above is a very simplified ViewController that demonstrates basic binding ability in iOS. To see more complex examples, please refer to the MvvmCross-Samples repository in GitHub.

So that’s Data Binding in a nut shell. There’s a ton more to it that I haven’t mentioned such as binding modes, value converters, binding languages, and more. I want to keep it simple for this post, but please feel free to read MvvmCross’s Data Binding doc to see all of the cool things you can do.

Navigation

Easily the second best perk of MvvmCross is ViewModel navigation. I will be writing an entire post just on navigation in the future, but essentially it allows you to navigate between ViewModel’s in your Core code so you can share navigation logic between platforms. MvvmCross supports a variety of navigational paradigms of each platform out of the box (Tab Bar, Nav Drawer, etc.), and provides you all the tools you need to customize them as you need as well.

To build off the above Data Binding example, we’ll bring the user to a new loading page when they click submit. So, we’d create another ViewModel and View as normal, but we’ll switch out the ICommand event method to utilize the NavigationService provided by MvvmCross.

class MyViewModel : MvxViewModel

{

private IMvxNavigationService _navService;

public MyViewModel(IMvxNavigationService navService)

{

_navService = navService;

SubmitMessageCommand = new MvxAsyncCommand(() => SubmitMessage());

}

//ICommand that we register a new command for in the constructor that will get binded to in the View

public ICommand SubmitMessageCommand { get; private set; }

private async Task SubmitMessage()

{

await _navService.Navigate<LoadingViewModel, string>(SubmitMessageCommand);

}

}

In the above example, we’ve now swapped the service to the IMvxNavigationService and we’re calling Navigate, providing the ViewModel and string generic type arguments, as well as a string object. What this will do is bring the user to the next ViewModel, which then finds and creates the View corresponding to the ViewModel, and passes the data into the LoadingViewModel. So, now our LoadingViewModel can take the text and whatever other data we want to pass and handle it accordingly. You can pass in any object type you’d like, I’m just using a string for this example. You can also Navigate and specify a return type. This allows you to Navigate to a new screen, gather some data, and return back to the ViewModel with the data. This is helpful for bringing the user to a text input screen, or some sort of selection screen and applying it to the previous screen once finished.

You can also customize and add additional behavior for both iOS and Android using custom presenters. I’ll discuss these in the future Navigation post. To keep it simple, I’ll end here on Navigation and save extra information for the Navigation post.

Inversion of Control and Service Locator Pattern

If you’ve looked at any of my above ViewModel examples, you may have seen me specify an interface as a constructor argument. One of the powerful features of MvvmCross is the built in Service Locator pattern. What this allows us to do is register an object against an interface, and the framework will automagically inject the correct object into the ViewModel for me. This also means we’re supporting the Inversion of Control (IoC) design principle which is great. If you’re not familiar, IoC is basically removing the need for a class to know who or how something is implemented. So, in the above Navigation example, MyViewModel doesn’t know what object it’s getting for Navigation, all it knows is the contract based on the interface. It could be getting MvvmCross’s MvxNavigationService, or maybe SuperAwesomeNavigationService. The whole goal is that MyViewModel doesn’t have to care or know exactly what it’s getting, just as long as that thing abides by the contract in the interface.

In order to register and then recieve objects through the Service Locator, we must interact with the IoCProvider Singleton provided by MvvmCross. I’ll show this in a code snippet below. These registrations would usually be done during startup lifecycles in the app, but we’ll just put them in a few methods for brevity sakes.

public void RegisterServices()

{

//Create a new Foo, and register it as a singleton against the IFoo interface.

Mvx.IoCProvider.RegisterSingleton<IFoo>(new Foo());

//Let MvvmCross create a new instance of Boo for you, handling any dependencies of Boo, and register it against IBoo

Mvx.IoCProvider.RegisterSingleton<IBoo, Boo>();

//Everytime someone resolves IBar, they'll get a new instance of Bar

Mvx.IoCProvider.RegisterType<IBar, Bar>();

//Only creates a LazyFoo object if someone tries to resolve ILazyFoo. Helpful to reduce registration time up front and saves on memory.

Mvx.IoCProvider.LazyConstructAndRegisterSingleton<ILazyFoo, LazyFoo>();

//Doesn't register anything, but will create a Boo instance, resolving any dependencies of Boo for you in the process.

//For example, if Boo's constructor was Boo(IFoo foo), it would determine it needs an IFoo via reflection, and will resolve IFoo and pass it into Boo for you.

var boo = Mvx.IoCProvider.IoCConstruct<Boo>();

}

public void ResolveServices()

{

//Returns the pre-created Foo instance we registered from above. Since it was registered as a Singleton, it will always be the same object.

var foo = Mvx.IoCProvider.Resolve<IFoo>();

//Returns a new Bar instance each time we call Resolve.

var bar = Mvx.IoCProvider.Resolve<IBar>();

//Will create the LazyFoo during the call and register it once we call it. Any future calls will get the already created instance.

var bar = Mvx.IoCProvider.Resolve<ILazyFoo>();

}

Converters

When utilizing Data Binding, you’ll find yourself wanting to convert the bound data before it shows on the View. A simple example of this is visibility. On Android, visibility isn’t a true/false, it’s one of three types: Visibile, Invisible, and Gone. This is exposed in the Xamarin.Android framework as Enums. So what if we want a boolean property in our ViewModel called ShowButton that’s just true/false that we can handle the logic of whether or not to show it in a cross-platform Core project? Simple, we would create a ValueConverter that we’d bind and pass in the ShowButton property. Each platform type would create their custom handling of the ValueConverter, but we can keep the logic in the Core project. Thankfully the MvvmCross framework has a variety of built-in Value Converters, visibility being one of them.

So, here’s how we’d setup the Visibility binding on each platform. First is Android through the axml file, and second is iOS through fluent binding in code.

<EditText

android:layout_width="300dp"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

local:MvxBind="Text MessageFieldText; Visibility Visibility(MessageFieldVisible)" />

public override void ViewDidLoad()

{

var set = this.CreateBindingSet<MyView, MyViewModel>();

set.Bind(_messageField).To(vm => vm.MessageFieldText);

//we're adding the "WithConversion" to pass in the proper type for the Visibility flag of the UI Control.

set.Bind(_messageField).For("Visibility").To(vm => vm.MessageFieldVisible).WithConversion("Visibility");

set.Bind(_submitButton).For("Title").To(vm => vm.SubmitButtonText);

set.Bind(_submitButton).For("Clicked").To(vm => vm.SubmitMessageCommand);

set.Apply();

}

Above is a platform specific converter for the UI. There’s many other converters that exist for the UI, such as Color converters, Language converters, and more. You can also use converters for something simple like abbreviating a name if the ViewModel property is too long, or converting a DateTime object to a readable string.

You can of course also create your own custom converters by creating a class and inheriting from MvxValueConverter, passing in type arguements for the type coming in, and the type going out. For example, if you wanted to convert a DateTime in your ViewModel to a string to display on a label, you’d create a class, inherit from MvxValueConverter<DateTime, string> and override the Convert method. Below is a simple example.

public class DateTimeValueConverter : MvxValueConverter<DateTime, string>

{

protected override string Convert(DateTime value, Type targetType, object parameter, CultureInfo cultureInfo)

{

return value.ToString("dddd, dd MMMM yyyy");

}

}

As long as you name your converter ending with “ValueConverter”, MvvmCross will automatically find and register the converter for you. If you want to name it differently, you’d need to override the FillValueConverters method in Setup.cs and add it to the registry.

Testing

Building off of the Inversion of Control section above, MvvmCross provides some nice support for unit testing through IoC supporting tests. Since our ViewModel’s are set up already for Dependency Injection, we can simply Register our test objects and MvvmCross will automatically handle injecting those into the ViewModels or other classes through IoC.

Utilizing the IoC support pieces of MvvmCross alongside the Moq framework will allow easy and fast unit testing of your application.

Another neat part of this is you can actually unit test Navigation. You’ll need to do a small bit of setup by registering an IMvxViewDispatcher as well as an IMvxMainThreadDispatcher, but you’ll be able to unit tests NavigationService method that occur in your ViewModel’s and services.

Cons

As with any framework, there will always be a few cons. Some of the things that I’ve ran across over the couple of years that I’ve used the framework are:

- Defects within the Framework, especially within some of the Android and iOS View’s that support binding. Keep in mind it is open source, and you can always open Pull Requests, but it’s worth mentioning.

- Startup Speed. It’s significantly slower than your average app due to a lot of the reflection based mechanism’s that run during startup. Some of the slowness exists just in Xamarin apps in general. It’s a small price to pay for the benefits though.

- Upgrade Pains. Some of the major updates to the framework completely overhauled namespacing and behavior, but didn’t do a great job documenting. This resulted in a long upgrade process and some pain in finding answers to problems.

- Documention. It’s not terrible, but it’s not good either. Spelling mistakes are common, with lack of reference material or broken links. Being open source, I usually end up walking through the MvvmCross code itself as my documentation to find the “real” answers.

- Outdated Samples. There’s a nice repository full of samples, but many haven’t been updated in years and aren’t relevant for the latest versions of MvvmCross. There’s really only 2-3 examples that are somewhat actively upgraded and worked on.

Recommended Material/Books

Mvvmcross is a very extensive framework, and it also requires a good amount of knowledge of Xamarin to be truly fluent with it.

If you’re somewhat new to Xamarin or MvvmCross, or maybe are only strong on one platform (iOS vs Android), I highly recommend picking up the book Xamarin in Action. It covers things such as the MVVM design pattern, MvvmCross fundamentals, creating iOS and Android layouts, asychronous best practices, unit testing, and even automated testing with the Xamarin.UITest framework.

There’s also a Xamarin Chat Slack with a dedicated channel for MvvmCross. I’m actively contributing and answering questions alongside other talented engineers. Some of the main contributors of MvvmCross also are actively engaged in the Slack channel.

MvvmCross’s main documentation is pretty helpful, but you’ll run into a few articles that need some TLC. It’s a great place to start to be used in conjuction with the MvvmCross sample apps.

You’ll also run into various blogs, articles, forum posts, and websites along the way with helpful material.

Conclusion

In my opinion, if you’re using the Xamarin framework, there’s really no reason not to utilize an Mvvm framework such as MvvmCross. It will speed up your development time, increase code sharing, reduce boilerplate code, and more. It’s also much easier to have some general .NET developers or C# guru’s that can write core code, and have some people who specialize in writing the View code on each platform. This reduces the need to have seperate talent to write Kotlin/Java and Swift/Objective-C code for example. It also means you can write your business logic once and share it between platforms which is extremely beneficial. If you have the financial means and time to write apps using their more native approaches, I would always recommend that over utilizing Xamarin purely from an app size and speed perspective.

Comments